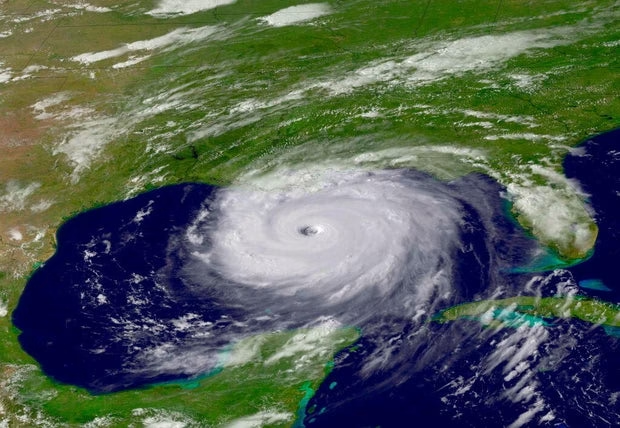

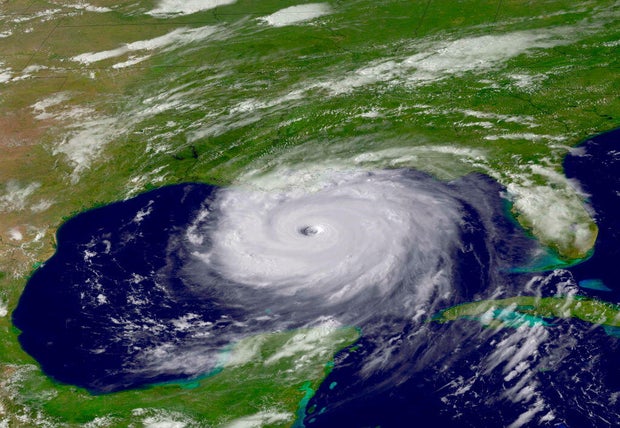

Hurricane Katrina was described as “a slow-motion catastrophe” on “60 Minutes” on Sept. 4, 2005, six days after slamming the Gulf Coast. Twenty years later, the storm is known as the costliest and one of the deadliest to ever hit the United States.

Katrina first made landfall as a Category 1 storm in Florida on Aug. 25, 2005. It then intensified to a Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf. Weakening to a Category 3, it made landfall again on Aug. 29, 2005, in southeast Louisiana and then in Mississippi.

While the toll didn’t become clear for days, the storm ultimately led to nearly 1,400 deaths, the majority in New Orleans, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Initial reports suggested the damage in New Orleans wasn’t worse than past hurricanes the city had weathered — until the levees failed.

“That’s when all hell broke loose, when all the water started inundating the city,” Eddie Compass, the New Orleans Police superintendent at the time, told CBS News in a recent interview. “That’s when we knew we had something that was much different than a regular hurricane.”

At least 80% of New Orleans was flooded. Roads were impassable without boats, and people were stranded on roofs.

AFP PHOTO/POOL/Vincent Laforet via Getty Images

Smiley N. Pool/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

Thousands of people had taken shelter in New Orleans’ Superdome ahead of the storm, but became trapped there for days with limited food and water when the city flooded.

Thousands more ended up on the interstate after escaping rising waters. They were stuck in the heat with no help for days.

Many weren’t able to evacuate ahead of time.

“We don’t have transportation. I mean, we’re living paycheck-to-paycheck,” one woman told CBS News as she stood on the side of the highway on Aug. 30, 2005.

Chris Graythen / Getty Images

Marko Georgiev / Getty Images / Marko Georgiev/Contributor

Vincent Laforet/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Michael Appleton/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

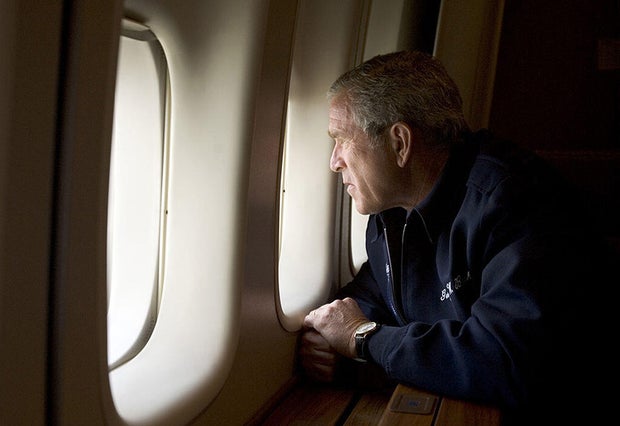

The federal response to New Orleans was harshly criticized for taking too long. It was three days before the National Guard arrived.

When then-Army Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré — who led the military response and has been credited for bringing calm to a chaotic situation — arrived in New Orleans, he faced a humanitarian crisis.

“I saw people waiting to be evacuated. I saw elderly people on the sidewalk. I saw women with babies there,” he told “CBS Evening News” co-anchor Maurice DuBois.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Mario Tama / Getty Images

Paul Morse/White House via Getty Images

Search and rescue operations and evacuations were hindered by several factors, including a broken communications grid, Honoré said in an interview with CBS News.

“Katrina overmatched the infrastructure. It broke the communications grid,” he said. “So that was a major challenge to find out exact situation reports, and many people in Baton Rouge and at the federal government were getting their information from watching television.”

An exaggerated picture of lawlessness also complicated the situation, Honoré said.

“This ended up being a major evacuation operational logistics issue, which was distracted by many political-inspired news that this was a looting problem and not an evacuation problem,” he said.

David J. Phillip/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Keith Birmingham/MediaNews Group/Pasadena Star-News via Getty Images

Mark Wilson / Getty Images

Storm surge from Katrina also devastated parts of Mississippi and Alabama. Images showed buildings reduced to rubble and debris across the coast.

One man in Gulfport, Mississippi, recounted to CBS News days after the storm hit how he stood on his stove as water filled his kitchen.

Barry Williams / Getty Images

Marianne Todd / Getty Images

Oscar Sosa/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Kari Goodnough/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Today, some communities, including Dauphin Island, Alabama, are still fighting to protect themselves from the next disaster.

Residents of New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, a predominantly Black community that was fully inundated when the flood wall broke, say the historic neighborhood has never returned to what it was before Katrina.

“We’re the land they forgot about. We’re the last ones to get our streets fixed, the last ones to get any kind of help from the city. If you come through here at night it’s dark — there’s no street signs, no working stop signs, there’s nothing down here. Two stores and one elementary school in the whole neighborhood, when there used to be tons of resources,” Ethelynn and Michael Vaughn told Getty Images.

Another resident, Frank Parker, said the neighborhood “still looks like a dead zone.”

Mario Tama / Getty Images

Brandon Bell / Getty Images

Brandon Bell / Getty Images

Brandon Bell / Getty Images

Kati Weis

contributed to this report.